I don’t do these often anymore for lack of time, and perhaps this one has no need of my take. However, Nope could easily be Jordan Peele’s best film yet. It was well acted, excellently scored and just as cinematically thrilling as Get Out. And if not, then more so. Also, I’d say just as heady and rich in subtext as Us. Therefore, Nope deserves to be reflected upon, and reflect upon it I shall.

Peele is becoming one of those rare and special directors like David Lynch, Spike Lee or maybe Tarantino (?) who makes films an experience in themselves. Thankfully he isn’t giving in to the rather “spectacular” nature of popular “Disney Epics” or “High-brow”, “Hollywood romances”. Cinema is probably the most “concentrated” expression of “the spectacle”, but, nope. Nope is more than mere “immediate gratification”. It’s rather a carefully crafted piece of cinematic excellence, made to be uneasy, self reflective, and full of complex irony. He grounds the piece deep within the sublime embrace of nature with wide shots of the environment. A Western wilderness on the outskirts of a Hollywood studio. A profound exposure to the beautiful and the visceral. And through the encounter with the Real, we come into contact with something “foreign”. Now, due to my own lack of time, working on editing Inferno, as well as developing a series of other connected stories for the Multiverse War Chronicles, I will be breaking my somewhat scattered streams of conscious into four, short, bolded sections for simplicity. So without further ado, SPOILERS AHEAD:

1st stream: The Spectacle is alive and well

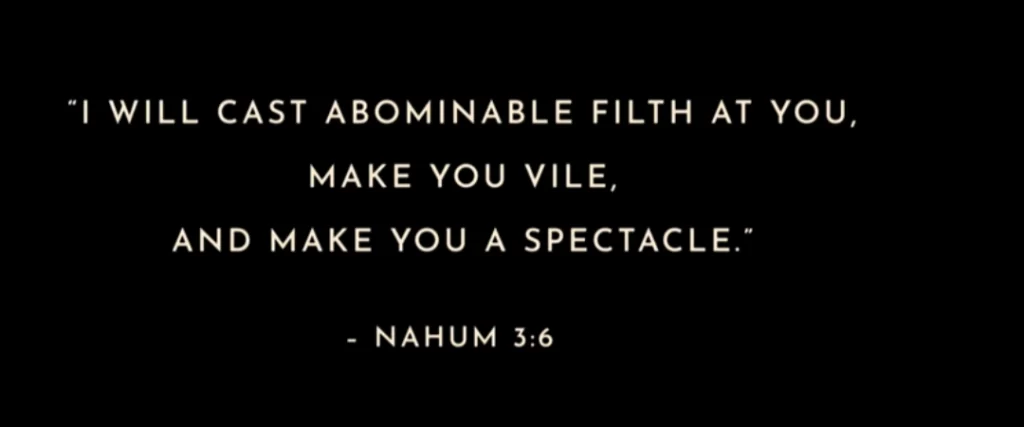

The film opens in fragments—two separate moments of tragedy and trauma—first in sound over a disconnected visual: the Universal-logo circling the planet earth—followed by the Monkey-Paw brand introduction: the paw, floating on air, stirring tea on a train. Behind that we hear a birthday party on the set of a sitcom. Then the lights go out and the quote in the image above appears on screen (Nahum 3:6). We hear the pounding of flesh and see for a brief moment the chimp covered in blood, crawling over a messy set. He sits for a moment, anxious and somewhat confused. He touches the foot of a body on the floor, perhaps checking for life. He then snatches his birthday cap off before turning to the camera. The film follows with the image of the wilderness at sunrise, right into the early day; men at work on the ranch. We witness the mysterious death of the protagonists’ father Otis Haywood Sr, struck down by a nickel in a volley from the sky. The next image, during credits, follows a tubular exit from the eye of the film’s “antagonist”, or a camera lens. The film begins explaining subtext at this point, and therefore I identify this “exiting of the eye” as the theoretical beginning of the film. What follows is an attempt at explaining, and/or reconciling the image that shattered the symbolic. The reestablishment of order beyond the “spectacular gaze” is necessary in order to bring “reality” back to these victims of tragedy.

As we peer in through the looking glass, we become disoriented by the symbolic excess, which absorbs the subtext as if it were light-rays in dark pigment. It’s weird and somewhat elusive. We’ll need to take our time digesting it afterwards as the shining light results from the reflective—pun intended—a process in itself. The authenticity of this piece of art returns in spite of the pale imitation Hollywood once told us was the real thing. The next scene of the film takes place years after the tragedy and Peele begins to offer context. A Black person on a horse (named Alistair E. Haywood) is claimed to be the first cinematic image ever to be seen. His great, great descendent, was Otis Haywood Sr, now succeeded by the film’s heroes Emerald (Em) and Otis Jr (OJ). They still work in the industry their father gave his life to. OJ presents the spectacle of a horse before a green screen. I imagine, on the green screen, OJ and Em’s house behind them out in the wilderness. Sis does the “song and dance” and presents business for hire. It’s immediately established that these siblings need each-other, as they both hold a key part to what made their dad who he was to Hollywood. OJ manages the horses and Em sells the spectacle. Though there’s a tenseness in the air of the scene, it all seems to be going well until their horse, ironically named Lucky, has a “visceral” moment due to forces of nature, and OJ/Em loose the gig. Even then, they can’t quite escape the eye in the sky. The spectacle is a powerful force.

2nd stream: Jupe & Gordy

It seemed everyone was having a good time until the chimp went berserk and began violently slaughtering his co-stars on set—a visceral intrusion of something animal. A kind of moment of truth, hidden behind the lie created on screen. And though there’s a difference between the horse and the monkey, I felt they both symbolized alienation and exploitation. What we’ve seen on screen ever since the formerly nameless African-American “movie-star”, Alistair E. Haywood. A deadly alienation, which on occasion bites back. Gordy the chimp, like Ricky “Jupe” Park, is present for the sake of the spectacle of difference. Jupe is the only Asian member of an otherwise white family on a sitcom named after a chimp. Gordy is the only monkey of course, though both he and Jupe share this characteristic Otherness which becomes their spectacle. They are exploited like props. This I believe, is the significance of Jupe’s fist-pump with the chimp following the massacre. Though it was a trademark of the show, in this real, off-camera context, it’s almost as it were, an act of solidarity. Though it seems it went completely over the child’s head. The horse on the other hand represents the first time the instinct is tamed by the Other. So the horse for me represents the “wild tamed” and Jupe Park is something of a fake “horse tamer”.

Jupe is an adult in the present time of the film. As an extension of the studio’s power, he runs the Sci-fi/Western-themed amusement park “Jupiter’s Claim” (a fascinating way to symbolize the spectacularization of Jupe via his nickname). As he returns from a far off glance and a memory of his tragic past, he’s greeted back to the world by his wife’s gentle touch. She places his hat back on his head as the image returns, preparing him to go out and put on his final performance. Earlier in the film, OJ and Em visit to sell Lucky to Jupe’s theme park as another part of their spectacle. OJ called Lucky his “second best horse” who “lost focus”. Since he can’t fire himself, he’ll have to cut ties with Lucky, though he has intentions of buying him back eventually. Jupe shows off his memorabilia and success to Em who shows an interest in his stage persona. He clarifies for Em that Kid Sheriff was his first sitcom while Gordy’s Home was a spinoff. He then proceeds to share his room of unprocessed trauma, formerly hidden behind a wall marked by a framed Mad Magazine cover featuring a parody of the “Gordy’s Home incident”. He recounts the story of the massacre that made him one of only two survivors and an inheritor of a legend. The only other survivor being his now disfigured former co-star Mary Jo Elliot.

Jupe Park’s tragedy, now converted to spectacle, once made him 50K when a Dutch couple paid to spend the night in this special room. He laughs it off as if it were nothing. When Em asks him what “really happened”, he refers her to an SNL sketch which apparently made light of the event. He claims they “pretty much nailed it” better than he could. Though there’s an absurdity to this claim, in a weird way, the comedic account, which Jupe describes to Em, does have the semblance of truth. A monkey, taken from its place in “nature” who is reminded of his violent alienation by the word “jungle”, which repeatedly leads to “freak outs”. Jupe calls Chris Kattan’s performance as Gordy a “force of nature”, the spectacle having now absorbed and distorted the “real thing”. Just one example of its insidious nature, now embodied by the “otherworldly” antagonist of the film. In the spectacle, everything that was once directly lived recedes into representation, fragmenting the unity of being, and deceiving even the deceivers in an inversion of lived experience. Perhaps in this sense, Jupe can no longer express the memory in anything more than moving images you could watch on YouTube.

Though both of Jupe’s sitcoms lie, he reproduces Kid Sheriff in his adult life, while establishing a one sided relationship with a creature who views him as nothing more than food. He tried to present the spectacle to an audience, believing he understands, that he is “chosen” (his word), and that he and Jean Jacket have a trust. He essentially invited it, though he has no control over the spectacle. “You can’t tame a predator. You need an agreement with one.”

As the film progresses, it seems more and more that there’s this critique of the dangers of “image production”. Jupe even gives the “aliens” a name to go with the story: “The Viewers”—what we are while we’re ensnared. While it could appear he was ready to offer Lucky up as a meal, it is he who the “alien” consumes. Lucky survives to later be retrieved by OJ. The maintainers of the dangerous spectacle get eaten up because they don’t respect the images they make. They “look the spectacle in the eye” for the thrill, for fame, for money, or recognition, but subconsciously it’s as if they are drawn to its “mystical” power—longing to see the “Thing in itself“.

Park wants to buy the Haywood ranch as further property for the sake of the spectacle, but OJ refuses recognizing the value of his family legacy. They have “skin in the game” as Em put it. It’s something OJ won’t allow to just be consumed. This takes on a symbolic significance because OJ is an actual horse trainer, while Jupe is no more than a Hollywood imitation of a cowboy. Jupe neither tamed the monkey, nor the “alien” from the sky, though continuing the work of his “master”, he presents it in a “spectacular” show, as if he were its master. A survivor sucking the juice out of that which is saturated in “surplus value“. A super-soaked stuffed animal in the circus of an old western fairytale. He exploits the tragedy that traumatized him, putting humanity aside to continue serving the spectacle. So while he never looked the chimp in the eye and therefore managed to survive the massacre, his survival leads to a false sense of security. Ultimately his demise comes when he looks into the eye of the spectacle itself in the form of “Jean Jacket” in perhaps the greatest tragedy of the film. With him, go all those who paid their “hard earned money” to witness it—into the bowels of the beast. It’s funny to think, but perhaps if Jupe had dealt with his trauma, Jean Jacket would never have arrived that day to take them all away.

The Thing-in-itself is a beautiful thing, if you’d have truly found it, but if that’s the case, it’s thanks at least partially to a “higher power” than you. We’re all looking to fill an empty hole, while mis-perceiving its reality until the moment is with us. That bright light of “grace” that comes in the midst of darkness that brings us back to eternal youth. The Gordy’s Home massacre could have saved Jupe’s innocence in his child actor phase, but the spectacle took him first. His survival only marking him for consumption. Despite the Otherness of his difference, Jupe passively offers no resistance as it comes for him. Having assimilated himself to the “modal of Whiteness” to an almost comical extent (think modal minority), Jupe seems to embody a false sense of privilege and comfortable conformity to his place within the system. There’s a pride he carries, being the first Asian American on a sitcom, and there’s an irony in that. While he may have happily embraced the image of inclusion he represented on screen, none has completely transcended the barrier, and nor shall they enjoy the promised spoils until the bubble has been popped.

3rd stream: OJ, Em & Jean Jacket

An alien sits above on a mountain in plain site though only those native to the land know of it. Aside from Jupe, there’s his wilderness neighbors OJ and Em. They capture the image of the unmoving cloud on their cameras. It’s good footage, but “it ain’t Oprah” as OJ puts it. In order to break out of their place, they need to show the world something they’ve never seen before. Perhaps on some level, it’s a service to the world. An image necessary to see. Their quest takes on both a sentimental and a spectacular quality. In OJ we get the sentimental. He’s gentle with his horses. He respects these beautiful creatures and their nature. Though for Em, Jean Jacket represents the emanicpatory potential of the “spectacle” and the desire for recognition which in some sense she was still seeking from her father.

The world they come from is a difficult one, full of struggle. But while they struggle, the crowd that surrounds them are in a cloud—everyone mesmerized by the site of the spectacle. They name the alien Jean Jacket after their childhood horse who Em never got a chance to train. And Jean Jack was a wild horse as Otis Sr once said, “Some animals weren’t meant to be trained“. Since OJ was the elder and a boy, favored by their father, he was the one set up to succeed him. Em seems to bitterly reflect on this while OJ recalls his father’s hard-headedness and relates it to his sister’s. It appears there’s something of a pioneering spirit in that headstrong hustle. OJ seems to pick up on this as well and perhaps it is here when their ultimate fate is decided, as the task of catching the “necessary shot”, the one their father was looking for, belongs to the spirit of his daughter.

One still wonders of course, what exactly this creature is. OJ and Em’s sidekick Angel fires off a few popular theories on what “they” are. The “little guys with big eyes “. Some of these theories are explored in my own work. Either intergalactic travelers looking for peace, or futuristic humans come back in time to stop us from destroying the planet. Or their world killers. Maybe it’s some kind of portal. These days I tend to think in terms of inter-dimensional entities. This time the entity comes in the form of some sort of flying thing. A “monster umbrella” as Angel puts it. I wonder if it dropped that praying mantis on the camera for obscurities sake. Without violently beating the cast into submission, the extraordinarily well functioning machine/alien does its consuming via the seductive “eye”. It later regurgitates a blood rain following the cries of human suffering from inside. That and some now useless trinkets. The waste.

In OJ’s first up-close encounter with Jean Jacket, we can hear Park’s voice speak through a megaphone as if the spectacle in the air is echoing the surplus back at us with an ominous sense of danger. Then it goes silent and OJ is alone for a moment. While Em is in her zone back at the house dancing, OJ is out in the wilderness, looking for their horse Ghost. That vibration sent the horse into the wild and even in the silence there is presence. After his second encounter, Em wants to run, but OJ stands his ground and transcends the vibration through an acute feel for the pulse of “truth”. He continues to do his work like his father once did stating, “I have mouths to feed”. His sense of duty is what makes him unique and he is spared the despair for the sake of his “clean soul”.

OJ is the actual hero of this film in the classic sense. He has values and upholds them with a kind of calm. He knows his father changed the industry, and he can’t let that go. He never plays the monkey and only serves Hollywood out of necessity. He respects the sublime, proto-linguistic vibration you can only feel if you’re sensitive. It is, in a sense, so profoundly present in the very nature of secondary causes. Also in a bad miracle, as OJ calls them. The “private plain” blamed for the coincidental money-trash from the sky that killed his father. He saw something out there too quick to be a private plane. Em realizes he means a UFO. That means an opportunity to make money and escape the struggle.

Em needs to be blunt to get the famed cinematographer Antlers’ help, despite their lack of funds. He’s offered an opportunity to do a show about “reality”, not to be confused with the Real, which in affect “disengages” one from the reality of being. But Antlers isnt interested in “reality”, so OJ suggests she brand it as “documentary”. A genre that is assumed to capture something “real”. Antlers prefers this. He has already submitted himself to the false “dream … where you end up at the top of the mountain, all eyes on you”. He tells Em it’s a dream you never wanna wake up from, as if it were a warning. Something like the dream of a modern capitalist utopia (utopian-liberalism). A neoliberal fantasy play which perhaps falls under the category of what Slavoj Zizek termed the “imaginary real“.

After all these years, Antlers is still drawn to the Thing. Whatever it truly is. His life’s work has been to make the impossible, possible via cinema. Em sells it a second time:

“We need the impossible to be shot.”

“That’s impossible,” responds the cinematographer. While he does his work for a kind of enjoyment beyond the pleasure principle, he gives his life to his art as if it were a sacrificial act of worship.

Authenticity and cheap imitation play heavily in the film. Naturally, the heroes represent something of authenticity in a world being swallowed. Jean Jacket is mistaken for a cloud for months, though OJ and Emerald see it best. The spectacle relies on illusion and a kind of detachment from the visceral “truth” OJ and even Em seem to feel without putting into words. The symbol of the cloud itself represents something ungrounded, while the so-called “sky dancers” (aka inflatable tube men) blow in the wind and become “alive”. They’re used as a decoy for the “flying saucer”. Of these, Jordan Peele states that “they kind of represent another theme in the sort of exploitation of what’s beautiful and what’s natural, and the human imprint on our environment. In a lot of ways, they also come to represent the lost souls of the exploited.”

While on the one hand, the “alien” represents the spectacle, I also detected something of the “divine” hidden within the symbol. Not coincidently, the design of Jean Jacket was partially inspired by the biomechanical, “angelic” beasts of the anime Neon Genesis Evangelion (an inspiration for my own work)—hinting further at the nature built within “the mask” of the UFO. Some have even compared it to a biblical angel with its vast silky wing span as it moves through the sky. Over the course of the film it appears to have evolved from a simple flying saucer to something more complex. Perplexing, though very “real”. OJ respects the monstrosity while not succumbing to it. He shows bravery in the face of annihilation itself, in order to uphold human values like bravery and responsibility. An aspect of human authenticity.

In one scene in particular, we get to see OJ’s bravery first hand when he attempts to save the foolish TMZ reporter, named Ryder Muybridge in the credits after the photographer who captured the lost black horseman (Alistair E. Haywood). Before Ryder goes chasing a story into the belly of the beast, Em tries to warn him, but all he’s concerned about is uncovering what happened at Jupiter’s Claim. He has the nerve to call her a “nobody” for refusing his offer to put her on camera, and says it’s her “loss”. He then rides in his high-tech camera-helmet, on an electric bike right into an electrical field created by Jean Jacket and gets tossed from his dead machine. As he lays stunned on the road, unable to use technology, OJ tries to get the reporters eyes off the spectacle (metaphorically speaking) so that he can save him from being taken by Jean Jacket. But the reporter can’t see without electricity and he’s preoccupied with capturing the footage. It’s actually kind of hilarious, despite the serious tone. He begs OJ to take a picture, suggesting OJ make a name for himself. It’s as if he doesn’t exist if it isn’t on film, though ironically, OJ , being the one who remains grounded, is the only one who can truly see and who understands what’s happening, and yet he remains responsible and brave in the face of such folly. Unfortunately, Ryder’s fate had already been sealed by his own foolish choices.

In an era of social media and easy to spread information (including misinformation), the narrative of Nope couldn’t be more relevant. We don’t look into the spectacle’s eyes unless somewhere inside we want its attention. It makes us believe it will restore the image from fragmentation. The “one-eyed, one-horn, flying, purple people eater” relies on our endless desire. The alien tests the soul and deceives as the spectacle deceives. Only the strongest, those who adhere to the pulse, shall survive its deadly grip.

4th stream: sort of a conclusion

I thought the “vaporewaved” (chopped and screwd) “Sunglasses At Night” was a nice touch. Vaporwave after all is a genre that speaks directly to the spectacle. Also, there’s the most repeated line of the song featured in the movie which carries the title: “I wear my sunglasses at night”. This gives me They Live/Situationist, Society of the Spectacle vibes. I’m not sure about “I got five on it” but “sunglasses at night” definitely seemed to be more than “just a vibe”. In the the fantastic climax of the film, the vibe becomes “words” again, and the symbolic order is restored.

Shortly after the death of the Ryder Muybridge, Antlers, out of seemingly nowhere remarks “The light—it’s gonna be magic soon”. He’s referring now to the “magic hour“. A point in which he will be able to film the creature in golden lighting before being eaten along with his camera. “It’s gonna be alright Angel. We don’t deserve the impossible,” Antlers assures before heading to oblivion. Then, with its appetite wet, Jean Jacket turns its attention to Angel, who survives by the hairs of his chin and it feels like a miracle (not the bad kind). First he’s blown down a hill covered in tarp, and then, thanks to his quick wit he’s able to tie some barbed-wired fencing around his tarp in order to stay connected to the ground as Jean Jacket sucks.

The alien then moves to Emerald, lingering over her while she refuses to look up at it, instead looking down at the soil. OJ calls her to go for the reporter’s motorcycle while he gets back to his horse. The bike won’t start, but OJ whistles and puts the attention back on himself. As Jean Jacket hovers toward OJ, he slowly paces backward on his horse, giving Em time to start the motorcycle. There’s a beautiful moment where he and Em exchange glances, and he signals with his two fingers to his eyes, and she returns as if they have their eyes on one another. There’s a deep sense of recognition, and you can feel the love and care between them. It’s an emotionally gripping moment. OJ then turns back to Jean Jacket, now in its most elaborate form yet, projecting a greenish, tubular protrusion similar to what we entered through in “the film’s “theoretical introduction” (I mentioned earlier).

Finally, Em takes off toward “spectacle park” (aka Jupiter’s Claim) while OJ keeps the alien’s attention. She bursts through the caution tape, and makes her way to where she was never suppose to go. She releases the large balloon of a smiling cowboy into the sky and waits as the alien comes her way. She grabs a bunch of coins from the dirt, presumably dropped by Jean Jacket, and inserts them into the wishing well photo-booth. The alien takes the bait and drifts over to eat the balloon, which now floats in the clouds. Em turns the lever repeatedly, and manages to snap a shot of Jean Jacket just as it consumes the balloon.

Afterwards the alien floats off into the distance. It appears the helium rich balloon is too much for Jean Jacket’s digestive tract. Em watches as the alien appears to explode midair. Somehow, it still seems afloat. As the popped balloon falls, Jean Jacket presumably blows away in the clouds and back to the aether. As the power returns to the park, the prerecorded voice of Jupe returns from that slow-motion “sunglasses at night” vibe to normal, and a Spaghetti Western theme begins. Emerald’s picture pops out from a slot on the side of the well, still white (undeveloped). On the one side of the park, Em sees the arrival of the media with their cameras ready to consume. Meanwhile, Em closes her eyes as if making wish. And when she opens them, OJ appears “Out Yonder” from the settling dust as the theme music crescendos. He’s atop his horse, like a hero in a classic Western. Em sighs with relief before the camera’s focus takes the image of the now fully resolved photo of the alien above the well, ready to consume.

This climax offers a sense of closure for the Haywoods, a resolution for their trauma and all the necessary symbolic coordinates necessary to restore order/”reality”. Having captured the impossible shot, Emerald, as a Queer Black woman, becomes the most unlikely winner in the social scramble for recognition, her golden ticket to a “better life”, or so she thinks. Her victory was mildly foreshadowed earlier in the film when she and OJ came to the park to meet with Jupe. She quickly photobombed a bunch of guests who were doing their wishing-well photo. Her victory, is the successful capture of the image on that same well, certain to earn her deserved recognition. In our greater spectacle, her photo is likely to be swallowed right back up into the mess. Though it remains an image to be seen. She was not expected to be the star of the spectacle. Even her father, following the patriarchal culture we’re a part of, gave his son his own first name. What better a “Hollywood ending”, then a victorious subversion of expectation.